தென்புலத்தார் தெய்வம் விருந்தொக்கல் தானென்றாங்கு

ஐம்புலத்தாறு ஓம்பல் தலை.

Thenpulaththaar Theyvam Virundhokkal Thaanendraangu

Aimpulaththaaru Ompal Thalai (43)

A good householder has five duties to perform – towards God, his ancestors, guests, family and himself.

पितृदेवातिथीनां च बन्धूनामात्मनस्तथा ।

सत्कृतिर्धर्ममागेंण गृहस्थस्य वरा मता ॥ (४३)

पितर देव फिर अतिथि जन, बन्धु स्वयं मिल पाँच ।

इनके प्रति कर्तव्य का, भरण धर्म है साँच ॥ (४३)

ಪಿತೃಗಳು, ದೇವತೆಗಳು, ಅತಿಥಿಗಳು, ನೆಂಟರಿಷ್ಟರು ಮತ್ತು ತಾನು- ಈ ಐವರ ಋಣಗಳನ್ನು ಸಲ್ಲಿಸುವುದೇ ಗೃಹಸ್ಥ ಧರ್ಮದ ಮಹೋನ್ನತ ಕರ್ತವ್ಯ. (೪೩)

Höchste Pflicht ist, den fünf Wesen zu dienen: Geistern, Gott, den Gästen, den Angehörigen und dem eigenen Selbst.

அறத்தாற்றின் இல்வாழ்க்கை ஆற்றின் புறத்தாற்றில்

போஒய்ப் பெறுவ எவன்.

Araththaatrin Ilvaazhkkai Aatrin Puraththaatril

Pooip Peruva Thevan? (46)

If a person leads his life as a householder by performing his prescribed duties to the best of his ability, what more is there to achieve for him, by following the other paths?

गार्हस्थ्यजीवनं येन धम्यें मागें प्रवर्त्येते ।

किं वा प्रयोजनं तस्य वानप्रस्थादिना पथा ॥ (४६)

धर्म मार्ग पर यदि गृही, चलायगा निज धर्म ।

ग्रहण करे वह किसलिये, फिर अपराश्रम धर्म ॥ (४६)

ಧರ್ಮಮಾರ್ಗದಲ್ಲಿ (ಸಸ್ಮಾರ್ಗದಲ್ಲಿ) ಕುಟುಂಬ ಜೀವನ ನಡಸಿದರೆ, ಬೇರೆ ಮಾರ್ಗಗಳಿಂದ ಹೋಗಿ ಪಡೆಯುವುದಾದರೂ ಏನು? (೪೬)

Vermag einer das Familienleben in seinem dharma zu führen – was kann er dann in anderen Lebensformen gewinnen?

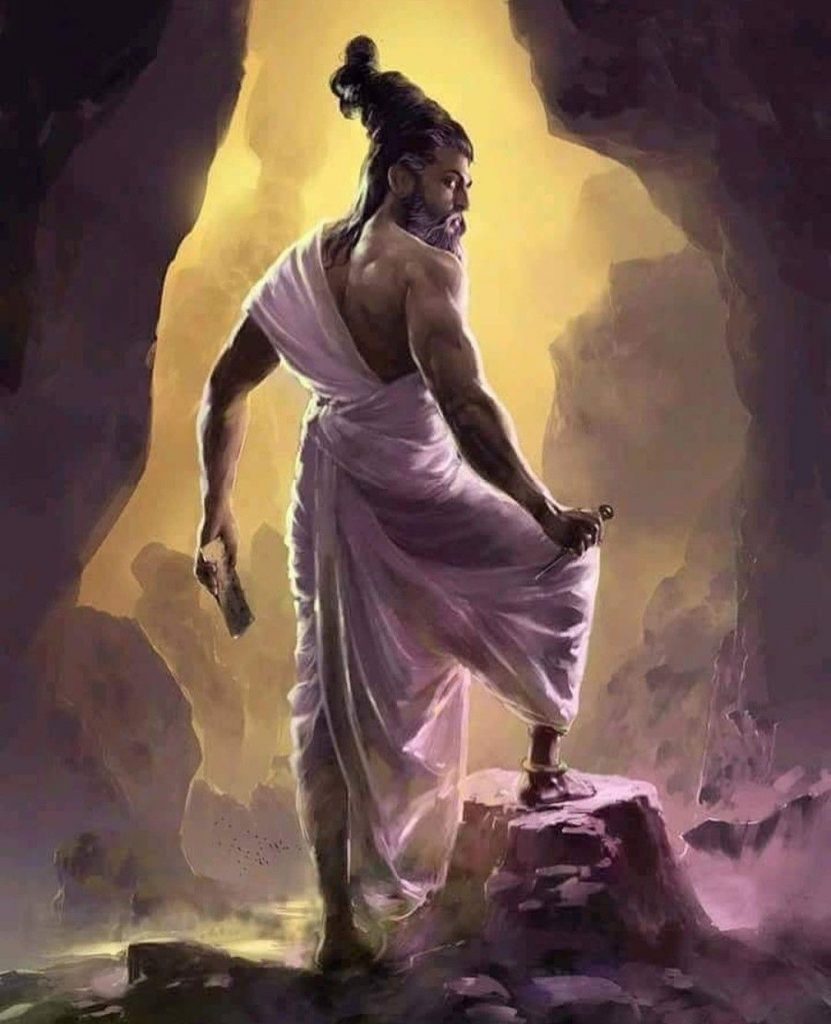

Most of us think that being spiritual involves growing a long beard, wearing white or saffron robes and renunciation of the world. Tiruvalluvar was probably among the first philosophers to advocate the life of a householder, placing it on par with the other ‘ashramas‘.

In ancient Indian society, the human lifespan was divided into four stages – Brahmacharya (student life), Grihastha (householder/family life), Vanaprastha (retirement) and Sanyasa (renunciation). It was generally believed that renunciation was the best path to liberation, and becoming an ascetic was a precondition to salvation.

Tiruvalluvar however, devotes a whole chapter of ten couplets to the life of a householder, arguing that as long as one carries out his duties to the best of his abilities, he also was on his way to salvation and greatness.

These duties are manifold. In those times, household income was generally distributed into five or seven parts. Some householders divided the income into five parts – one each for God (the temple), ancestors (offerings), family, friends and the self.

A renowned philosopher Purandara Dasa, recommended the seven-part method – one each for God (temple), a holy visit (teerth yatra), parents, charity, family, savings and self.

Valluvar implies that householders can treat their own house as a temple, and perform selfless duty towards those who he is responsible for, as his method to liberation. What a yogi or sadhu achieves by penance and renunciation, a householder can achieve through regularly performing his duties righteously.

Swami Vivekananda echoed these thoughts and added “It is useless to say that the man who lives out of the world is a greater man than he who lives in the world; it is much more difficult to live in the world and worship God than to give it up and live a free and easy life.”

न कर्मणामनारम्भान्नैष्कर्म्यं पुरुषोऽश्नुते |

न च संन्यसनादेव सिद्धिं समधिगच्छति || 4||

na karmaṇām anārambhān naiṣhkarmyaṁ puruṣho ’śhnute

na cha sannyasanād eva siddhiṁ samadhigachchhati

One cannot achieve freedom from karmic reactions by merely abstaining from work, nor can one attain perfection of knowledge by mere physical renunciation.

Srimad Bhagvad Gita 3.4