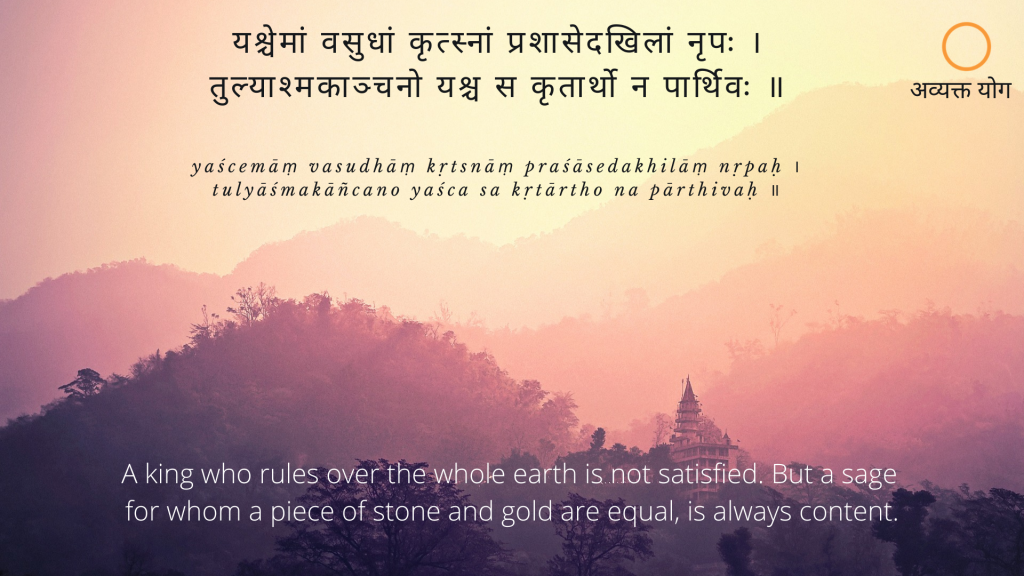

यश्चेमां वसुधां कृत्स्नां प्रशासेदखिलां नृपः ।

तुल्याश्मकाञ्चनो यश्च स कृतार्थो न पार्थिवः ॥

yaścemāṃ vasudhāṃ kṛtsnāṃ praśāsedakhilāṃ nṛpaḥ ।

tulyāśmakāñcano yaśca sa kṛtārtho na pārthivaḥ ॥

Mahabharata Shanti Parva 17.11

A king who rules over the whole earth is not satisfied. But a sage for whom a piece of stone and gold are equal, is always content.

Contentment is a very relative word. You may be content in eating rice and lentils, someone else, on the other hand, may want richer food. One may be content with a fan in summer, another may be content just having electricity.

So how do we define a common baseline – a minimum requirement for contentment?

चिन्तामपरिमेयां च प्रलयान्तामुपाश्रिता: |

कामोपभोगपरमा एतावदिति निश्चिता: ||

chintām aparimeyāṁ cha pralayāntām upāśhritāḥ

kāmopabhoga-paramā etāvad iti niśhchitāḥ

Bhagavad Gīta 16.11

They are obsessed with endless anxieties that end only with death. Still, they maintain with complete assurance that gratification of desires and accumulation of wealth is the highest purpose of life.

When we obtain what we want, we experience that relief, that high, for a few days. But then a new anxiety begins. We start worrying about it being snatched away, about us losing it.

Maybe I can draw a few learnings from my own example. About a year and a half back, I bought a shining new, fully loaded BMW 5 Series. Unique blue color, Nappa leather white seats, gesture control – the works. This, I bought by selling off a slightly older version of the same car. I was content…for a few days. Then the problems started.

No, don’t get me wrong. The car drove perfectly – a fine piece of engineering and German expertise. What went wrong was to do with me.

You would know the feeling if you have ever bought a new car. Park it anywhere, and the mind would be on whether someone would inadvertently scratch it, or worse, cause a dent. Every time I went for a movie, half my attention would be on my car in the parking lot. Once done, I would rush to the parking just to check if there was a scratch. Traveling with me was a task in itself – do you have clean shoes? No eating in the car, no drinking water lest it spills – the list was endless. There came a time when I realised that I wasn’t owning the car – the car was owning me.

My ‘The sādhakā who sold his BMW’ moment.

I sold the car, and now I drive an ordinary (but robust) Mitsubishi, with my mind at peace, and no tension of high EMIs. I take good care of the car, but I don’t go crazy about it. I am happier than I was when I drove the BMW, much happier. I am back to being the master. And my wife has started loving me again.

Jokes apart, this was a very big learning. We tend to place more importance on our possessions – house, car, television, even phones and laptops. A large part of our lives goes in first buying, and then upgrading these possessions, often on back-breaking monthly instalments. The two-bedroom flat you bought five years back is too small and too old – and it doesn’t look new anymore. Don’t get me started on mobile phones – a new model every year.

We just can’t stop – the more we get, the more we want.

The śloka draws our attention to this truth of life. Even a king who can possibly have everything that he wants, is still not satisfied. These is no end to our desire for possession, and it’s time we realise that. It is a never-ending road. Contentment comes from the realisation that material possessions don’t make us happy.

I don’t mean to say that we should not have any possessions and live like a sage in a forest – but we should not be tied down by what we possess.

Be it material goods, or be it knowledge. Earn more, learn more, but don’t be bound by it. Attachment is always accompanied by fear of losing. Set yourself free – life is meant to be enjoyed, and not an endless race to accumulate possessions, and worst still, be possessed by them, and not the other way around.